I’ve called Day 7 ‘Churches in Sussex’ for consistency but in fact it involved churches in Surrey and Hampshire! I had planned to visit Sussex churches but I decided to combine a visit to a friend in Hampshire. The first two churches are in Surrey and the others in Hampshire:

All Saints' Church, Little Somborne

The first church, St James, is in the picture postcard Surrey village of Shere which is between Guildford and Dorking. It was my first visit to the village and it certainly does live up to its reputation as a quintessential English village. Chocolate box buildings in the centre of the village and a stream with ducks.

St James church in the middle of the village dates to around 1190 and is cruciform in plan. The church is approached up a cobbled lane, though a lych gate designed by Edwin Lutyens in 1902. Lutyens designed quite a few cottages in Shere for the Bray family, hereditary Lords of the Manor. The walls are a fascinating jumble of materials, from re-used Roman tiles to clunch, flint, Caen stone imported from Normandy, Tudor bricks, and local stone.

The central tower dominates the surrounding period cottages. The base of the tower is Norman and the striking spire was built between 1213 and 1300.

Windows in the Lady Chapel and chancel contain fragments of medieval glass including arms of the Clare, Butler, and Warenne families. Other windows show the red rose of Lancaster, placed here when the Shere estate was owned by James, the 2nd Earl of Ormond, in the 15th century.

The square font made of Purbeck marble probably dates to around 1200 AD.

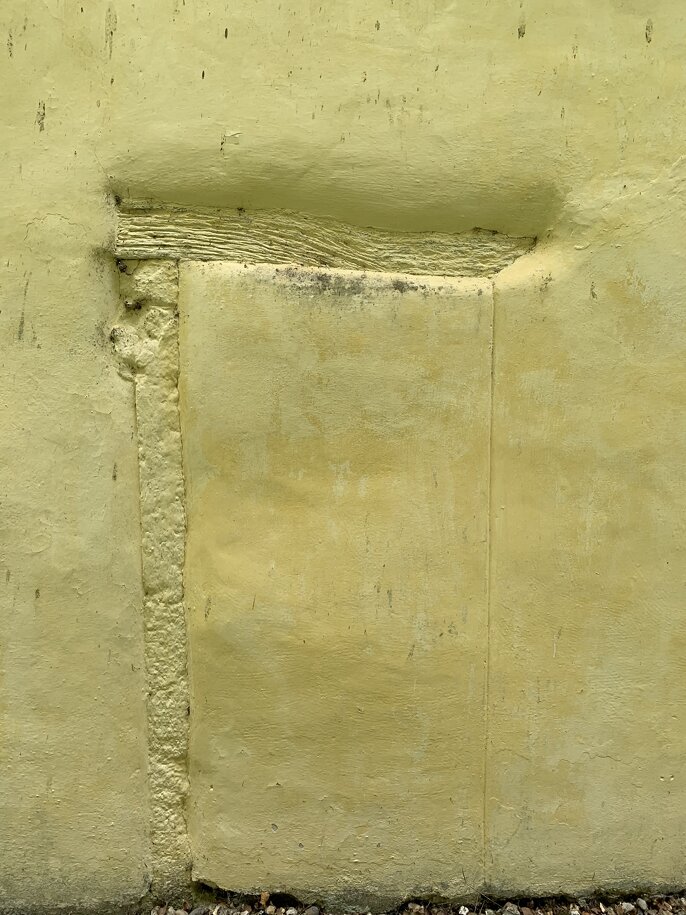

A quatrefoil opening in the north wall of the chancel once communicated with a small anchorite's cell linked to the church. The 'Anchoress of Shere' was Christine Carpenter, who was enclosed in her cell in 1329. She received gifts of food through a grate on the outside wall and could view mass at the high altar through a narrow squint and receive sacrament through the quatrefoil opening (images below).

A quatrefoil opening in the north wall of the chancel once communicated with a small anchorite's cell linked to the church. The 'Anchoress of Shere' was Christine Carpenter, who asked the Bishop of Winchester for her to be walled within a tiny cell in 1329. She received gifts of food through a grate on the outside wall and could view mass at the high altar through a narrow squint and receive sacrament through the quatrefoil opening.

After 3 years the Anchoress had had enough of her life of seclusion and she decided to leave her cell. To go back on her vows must have taken enormous courage, for it like an act of sacrilege. However in 1332 she asked the Bishop if she could return to her cell. He only agreed on the condition that she serve a penance in proportion to her sin (of leaving the cell) and if she didn’t ask for her penance she could be excommunicated. A fictionalised account of Christine Carpenter's life is told in the 1993 film Anchoress, starring Natalie Morse.

In the chancel are memorial brasses from the 15th and 16th centuries, including that of John Redford and his family. There are further brasses to John, Lord Audley (d. 1491) and Robert Scarcliffe, Rector of Shere, who died in 1412, and a 15th century brass to Oliver Sands is fixed to a window sill in the north transept.

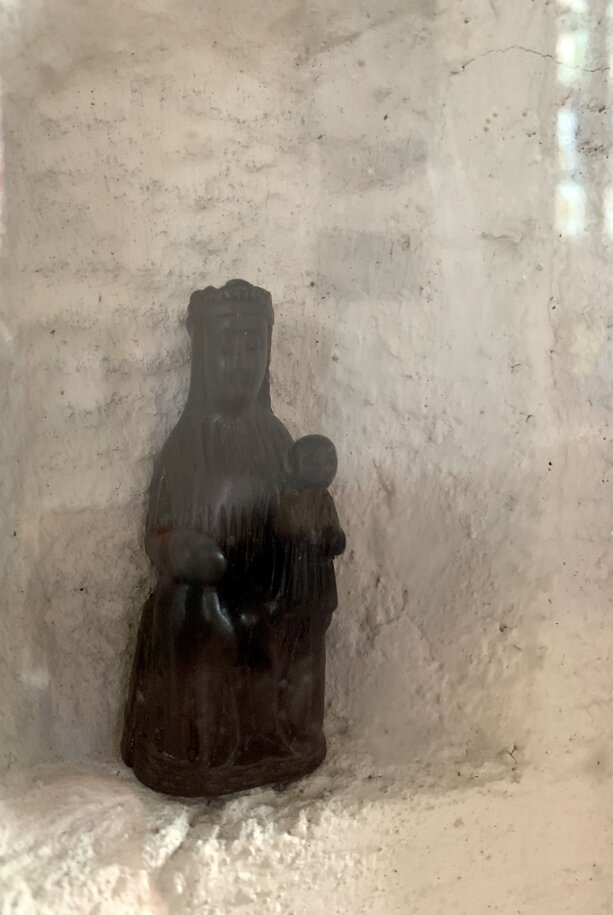

Another highlight is a 2-inch high statue of the Madonna and Child dating to 1300, thought to have come from a pilgrim's staff or a Bishop's crozier. This was dug up by a dog on Juniper Hill, Coombe Bottom, in 1880 and is very similar to one in the British Museum. It is not known how it came to be lost, or what its significance is, but it is a very fine piece of medieval craftsmanship.

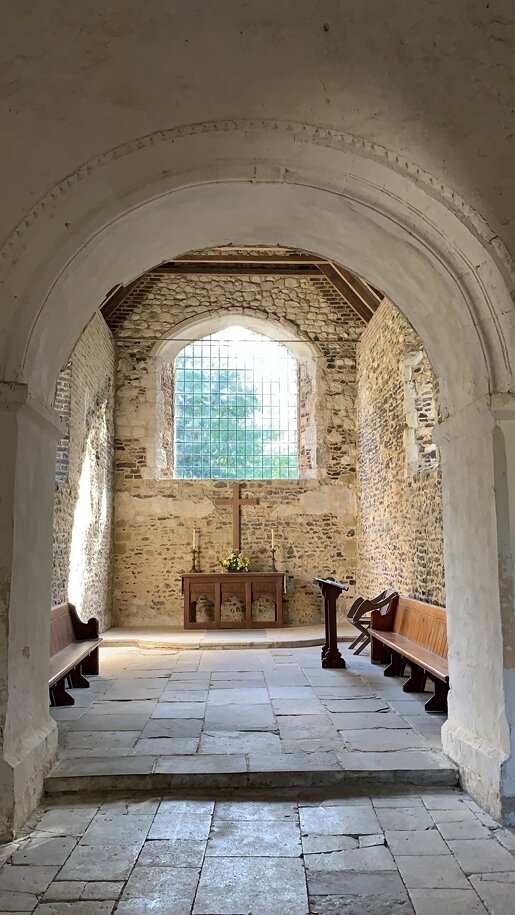

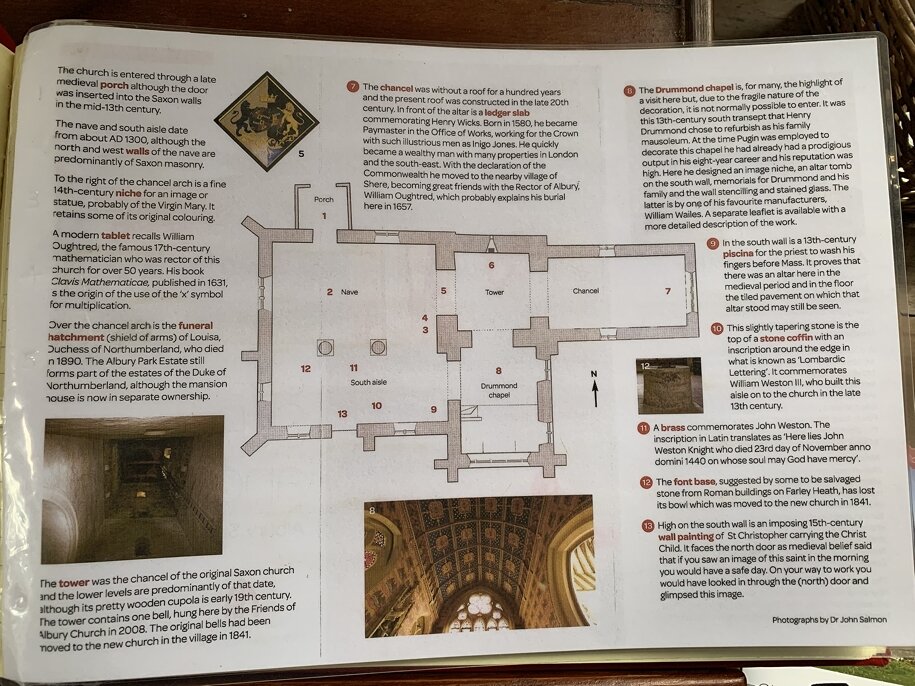

It was a five minute drive from Shere to the second church, St Peter and St Paul’s in Albury Park. This charming ancient flint-walled church dates back to Saxon and Norman times. It is in the most exquisite setting within the grounds of Albury Park above the River Tilling. You are immediately aware of the strange shingled dome set atop an embattled central tower.

The church has the most surprising, exquisite interior - limewashed and uncluttered. In the last image below you can see up into the bell tower.

The Saxon building was greatly rebuilt during the Norman period and features a 13th-century door. The most interesting bits of the interior are a 15th-century wall painting depicting St Christopher with a curly red beard and an ornately decorated south chapel.

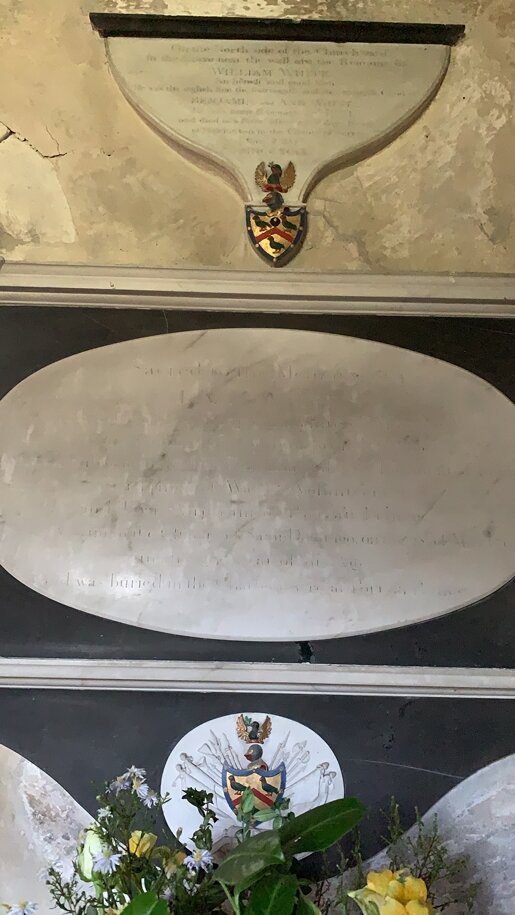

There are interesting monuments, including a brass of John Weston who died in 1440; an odd but delightful eighteenth-century shingled cupola over the tower.

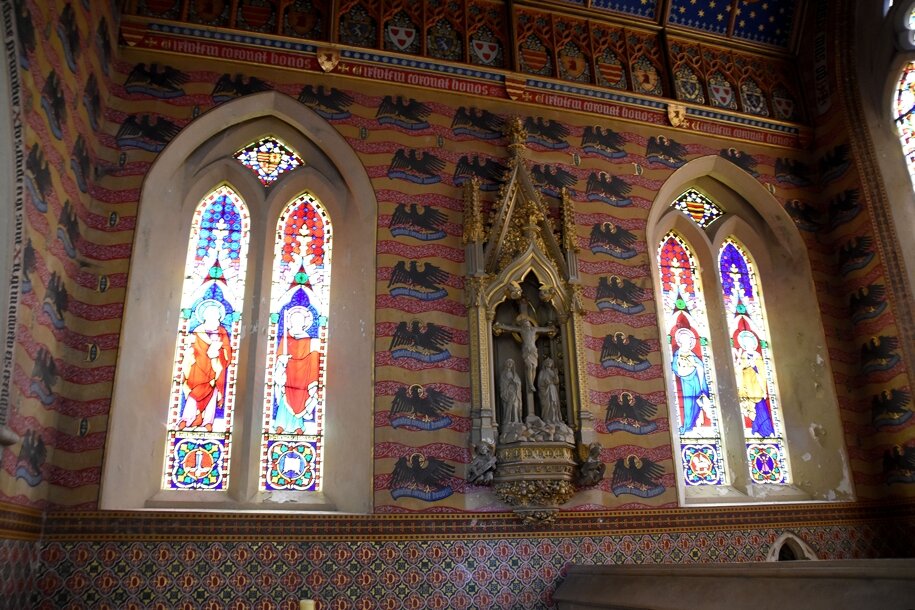

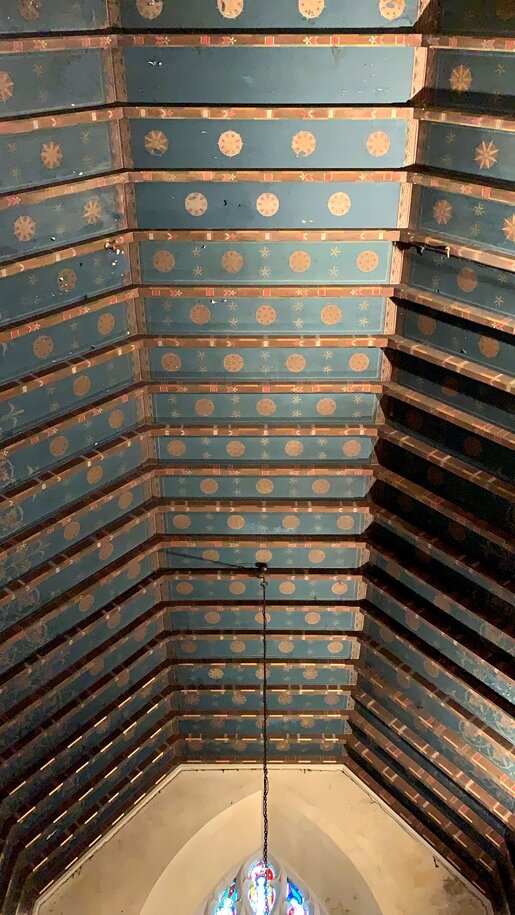

Another highlight is the South transept which was rebuilt by AW Pugin, the architect primarily responsible for the Houses of Parliament in London, to create a mortuary chapel for the Drummond family of Albury Park. The chapel in total contrast to the main part of the church features a richly tiled floor, colourful stained glass, painted ceiling and walls and numerous Victorian era Drummond memorials. The chapel is locked behind a slatted door so it is still possible to take pictures.

The font base was supposed to have been salvaged from Roman ruins on Farley Heath. It has lost its bowl which was moved to the new church in Albury village in 1841.

The church is no longer used for regular worship and is sparsely furnished which helps one appreciate the architecture. It is in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. Apparently it’s worth visiting in spring when the grounds of the church are covered with snowdrops.

It was nearly an hour to the next stop, the beautiful Georgian town of New Alresford, (pronounced Allsford) which for many centuries was a prosperous wool town. Old Alresford is mentioned in the Domesday Book but the present town of New Alresford did not come into existence much before 1200. The colour-washed Georgian houses you see today rose from the ashes of great fires in the 17th Century but many retain their original 13th century cellars.

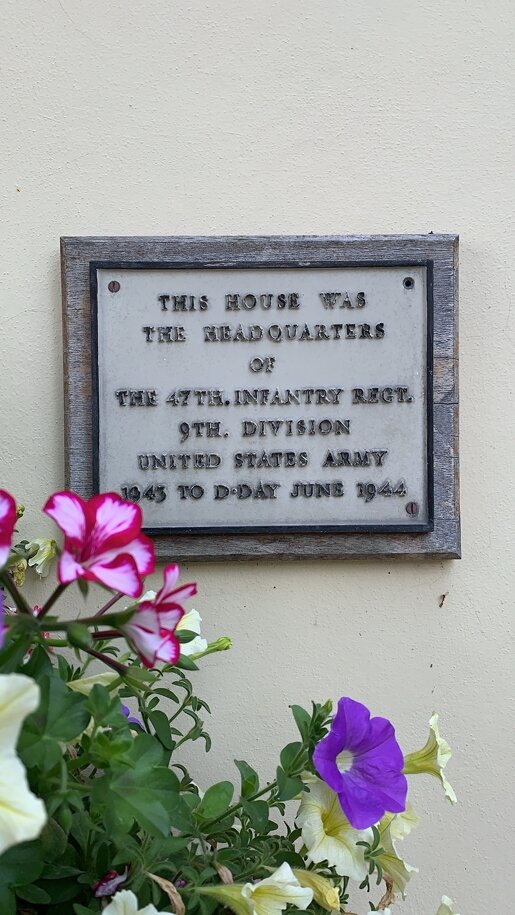

The town played host to the 47th Infantry Regiment, US Army from 1943 until D-Day 1944 who were headquartered in the house in the images below on Broad Street.

A few minutes outside Alresford is Long Barn, a one-stop shop for plants, interiors and a fantastic cafe, where I met my friend for lunch.

After lunch a half hour drive took me to the first of the four Hampshire churches I would visit on this day trip. All Saints, Little Somborne, is a real gem of a church and together with the next church in Kings Somborne a few minutes’ drive away, they are two of my favourites of all the churches I’ve visited this summer. Both are in exquisite settings and are simple, quite plain churches but therein lies their beauty.

All Saints sits in a rural location beside the grounds of Somborne Park in a downland valley. It is a single cell building (nave and chancel combined into one structure) and a small wooden bell turret at the west end. It dates to the late Saxon period but was greatly remodelled and extended in C12.

The building is of flint covered in whitewash inside and out. The material for the building is thought to have been brought here from Binstead on the Isle of Wight, probably because good building stone is not readily available in this area of Hampshire.

Mentioned in Domesday Book, it is half Saxon and half Norman: the Saxon church had a nave and chancel but in 1170 the Normans removed the latter and extended the church eastwards, doubling its original length and adding a tiny new chancel. Evidence of both periods is clearly seen in the walls, windows and doorways of the building. The Normans extended the nave westward and added an extremely tiny chancel, no more than a metre in depth. The current north and south doors are Norman, as is the chancel arch, which probably dates to about 1190. The church was beautifully decorated for harvest festival especially around the altar.

In the churchyard is the grave of Thomas Sopwith, the pioneer aviator who gave his name to the famous World War I fighter plane, the Sopwith Camel.

In the north wall are the remnants of a doorway thought to have linked the church to a 13th-century hermit cell, possibly belonging to Peter de Rivallis (d. 1226).

It is just a four minute drive to the next church, St Mary’s in Ashley, Kings Somborne. This little C12 church stands within the earthworks of a Norman castle, Gains Castle and the church was probably built to serve the castle. It’s a delightfully simple building consisting of only a narrow chancel, nave and south porch. There is no bell turret or tower but there are a pair of bells hung within a niche under the west gable of the nave.

The edge of the graveyard has glorious views of the Hampshire countryside.

The interior of the church has an unusual three-opening chancel arch, with large half-height squints either side of a narrow round-headed archway.

Another unusual feature is a Jacobean alms box crafted from an old oak post.

There is a small 13th-century wall painting on the inner splay of a chancel window depicting the figure of a man, though who it is meant to represent is not clear.

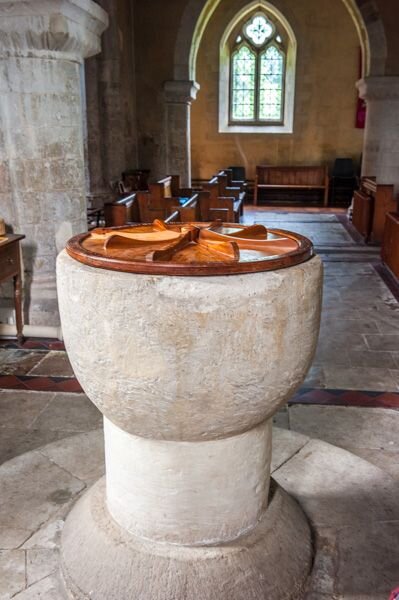

The worn font is Norman and carved from Purbeck marble.

By now I was slowly heading back to London but I still had two churches to visit along the way. 43 minutes from the last church took me to the village of Upper Farringdon and All Saints’ church. This is a C12 church restored and enlarged in 1858 by Woodyer. The walls are stone and rendered with a tile roof.

Inside, the arcade rests on circular piers, the western bay with scalloped caps, the eastern bays moulded and there is a small Norman north door which is blocked. The ceiling is flat between tie beams, but at the east end is arched with moulded wall-plates. The chancel is Victorian Early English. There is a classical wall monument (of 1770) in the nave, a panelled C18 pulpit, a bowl font meting on 4 C13 capitals, other fittings being Victorian. Gilbert White (of nearby Selborne) who was curate 1761-85.

Inside the church was a hive of activity for a wedding the next day. The bride, her mother, mother-in-law and other family and friends were decorating the church with flowers that they had all grown especially for the wedding.

This is Massey’s Folly across the lane from the church, You would not expect to find in the heart of a pretty Hampshire village! The building was conceived in the eccentric mind of a former Rector of Farringdon, although the building was never completed in his life time. It towers over the surrounding cottages making it look incongruous. It’s a Victorian confection of red brick and terra cotta tiles and sprouts in all directions incorporating numerous architectural features. For many years the Folly was at the centre of village life with the Farringdon Village School in the western part of the building and the village hall in the eastern half. Farringdon school closed in 1987 and faced with soaring costs, Massey's Folly was sold for development for housing in July 2015.

The last church, St Mary’s, was seven minutes away in the village of Selborne, famous for teh naturalist Gilbert White (his house is the first image below).

St Mary’s church stands on a rise of ground a short stroll from Gilbert White's house. The present church, built on the site of an earlier Saxon building, with its Norman tower and nave, largely dates from 1180. The church was greatly restored in the mid-19th-century by the great nephew of Gilbert White, the naturalist, who was Curate for many years until his death in 1793 and who is buried here.

The churchyard is beautiful some interesting gravestones and sweeping views over the countryside.

The nave is a symphony of Norman architecture with large cylindrical 12th-century pillars topped with simply carved capitals. The base of several pillars are carved with wings.

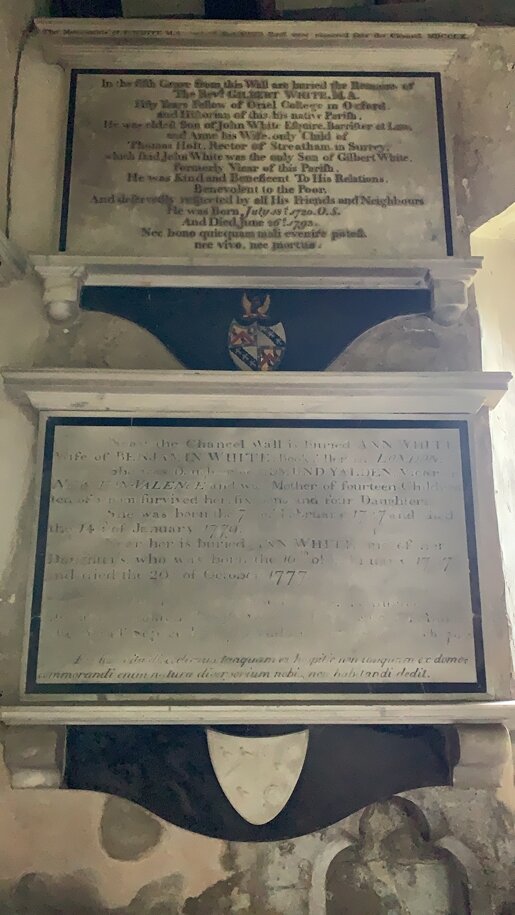

Most people visit the church for what lies in the chancel. Here you will find numerous memorials to members of the White family whose most famous member, naturalist Gilbert White, is commemorated by a wall plaque on the south wall. Gilbert White is actually buried in the churchyard outside the north wall of the chancel.

In the centre of the chancel, set into the floor before the altar, is a simple black slab to White's grandfather, also named Gilbert. The elder White served as vicar of St Mary's from 1681-1728.

The interior has two further outstanding historic features; above the altar is a triptych painted by Flemish artist Jan Mostaert depicting the Adoration of the Magi, dated to around 1515. The painting was gifted to the church in 1793 by Benjamin White as a memorial to his brother, the naturalist Gilbert White.

On the wall is a beautifully carved wooden panel showing the Descent from the Cross, also Flemish, from about 1520.

The south aisle was enlarged in the 13th century to allow space for a chantry chapel at the east end. To one side of the altar is a 13th-century piscina, while leaning against the wall are stone coffin lids bearing the insignia of the Knights Templar. The floor surrounding this south aisle altar is set with medieval tiles found during excavations of the Selborne Abbey site in 1953.

Gilbert White is commemorated by a glorious stained glass window depicting St.Francis. There is also a beautiful 800 year old font and a 17th century pannelled chest.

Any idea what this tree is? I couldn’t identify the fruit on it.

That was the end of my 7th day trip to visit little historic parish churches and the one and only time I ventured into Hampshire as my focus was on Sussex churches. However these gorgeous Hampshire churches didn’t disappoint and I would love to go back and search out more of them.

I am delighted to announce that in September 2019 I became a published photographer, that is, I had my first ever photographs published in a book, The Gardener’s Travel Companion to England, by well-known Australian author Janelle McCulloch which features a variety of beautiful English gardens.